Should the U.S. stop giving foreign aid?

This is a question many have been asking long before Elon Musk and Donald Trump launched DOGE (Department of Government Efficiency) and began dismantling USAID and its work around the globe.

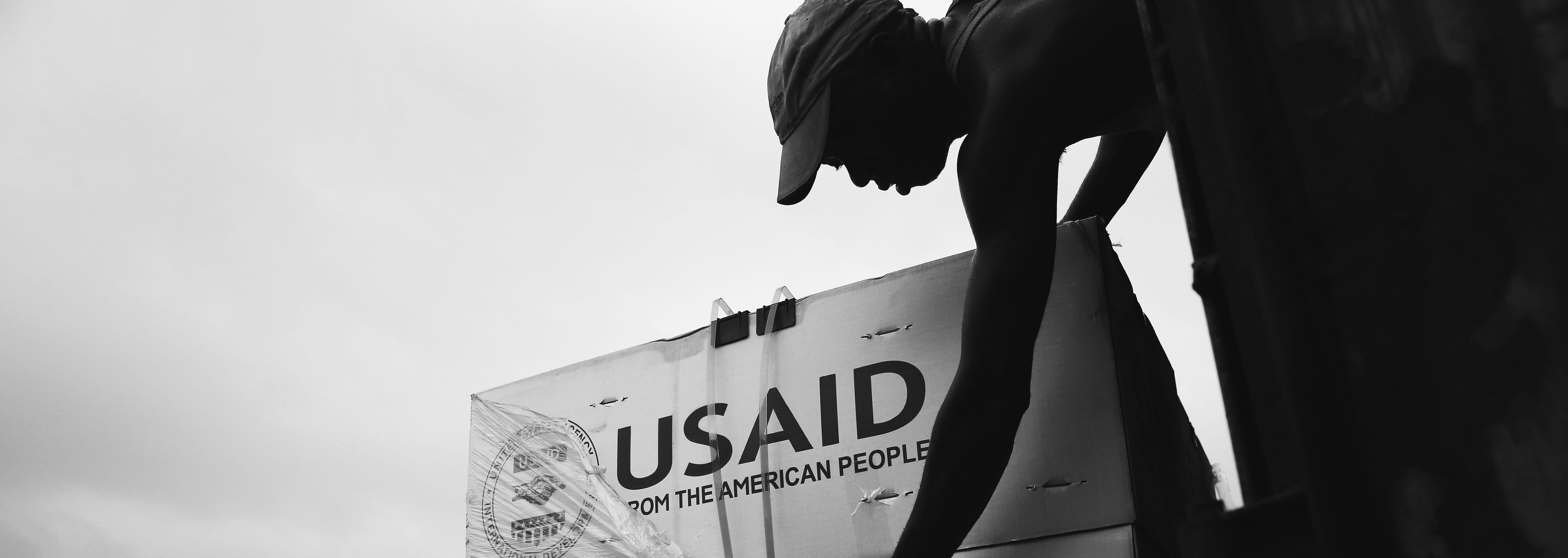

I’ve wondered about this myself. My reporting career began in South Sudan, where I witnessed the tension between the immediate, tangible benefits of foreign aid for individuals and its more troubling downstream effects. On the one hand, it was hard to ignore the sight of desperate, hungry families being fed by bags of food branded with the red, white, and blue USAID logo, or the health clinics delivering life-saving care that would otherwise be unavailable. But on the other hand, this aid was often exploited by corrupt local leaders to remain in power. And there’s the stark reality that after 40 years and tens of billions of dollars spent in Sudan, the country remains far from economic stability.

Critics of foreign aid, like Bill Easterly, author of The White Man’s Burden, and Dambisa Moyo, author of Dead Aid, argue that foreign aid often does more harm than good. They contend that the U.S. and other nations should radically rethink their approach.

But this winter, Donald Trump did something no one expected: he halted nearly all foreign aid and operations worldwide. Elon Musk even went as far as to call USAID a “criminal organization.”

In today’s episode, we’re joined by long-time international correspondent and host of NPR’s Rough Translation, Gregory Warner, for a deep dive into why USAID was founded in the first place, how it expanded into the massive program it is today, the consequences of freezing its operations, and an examination of the claims that USAID is part of a U.S. deep-state operation.

For the listener who’d like to hear more from Warner, he publishes a Substack newsletter called Rough Transition. His latest series explores words that have no direct English translation, like tamana, a Malagasy word describing the feeling of being deeply at home in a stranger's house. And if you reach out to him mentioning you're coming from Reflector, he’s happy to offer a complimentary six-month subscription.

As always, thanks for listening,

Andy (and Matt)

Thank you for this coverage of the USAID, as a (now unemployed) aid sector worker it was great to see this topic.

I think some discussions with current humanitarian and development workers could enhance Reflector’s coverage – I hope you might have further episodes on the topic. For example, the Kenyan woman interviewed. A development sector program person can pick up and explain a bit more nuance. The women referred to herself as a ‘person with a disability’. Your average person living in the foothills of Mt Kenya? Probably not using this type of language. She’s trying to hire other women, specifically. Why? That is an example of how USAID is a soft power that influences the lives, beliefs, and choices of people around the world. The programming generates goodwill and orients people towards US culture and values – in this case, the progressive ideology of the Biden admin. It’s about that as much as actual development outcomes. Yes, there’s a moral question around whether it’s right or wrong to exert this soft power - nowhere will you find people questioning that more than in the aid sector itself with its endless internal debates on decolonization and localization – but there’s no doubt it exists, it’s a primary reason for USAID’s existence, and the loss of this tool weakens America. Not to mention the demolition of the agency and how this lays a blueprint and sows fear throughout the federal government.

There’s also some commentary here around the post-dated cheque. Yep, not great to do that. But it’s also a reflection of how incredibly reliable the US has been seen as a development partner up to now. USAID was an incredibly coveted donor because of how reliable, trustworthy, and transparent the organisation is. Or was. This reputation is now lost. Another aspect of this is actually the bureaucracy of USAID. There are so very many checks and balances in place to ensure money is correctly disbursed that yes, it takes time. People have to wait to get the money until after the point in time they need to spend it, it’s not that conducive to taking advantage of entrepreneurial opportunities when they are present. For this woman, it manifested in writing a post-dated cheque because she doesn’t have any other funds to draw on. For organizations, it means they front the payments from their reserves and get reimbursed by USAID when certain milestones are met. This is the main problem right now – not only has work stopped, but the US has failed to pay its bills and left organisations in the wind, so months of operating costs not being reimbursed. See Devex reporting on this.

It was also a little frustrating to hear the episode fail to debunk the programming examples touted by the Administration in the sound bite early in the episode because I don’t think your average listener understand how inaccurate these example were as a snapshot of USAID programming. I think it was Forbes that went through each program (the opera, the plays etc) and put them in context, with only one being noted as a real problem. I could explain tons of ways I think programming and program budgets are getting out of control with ideologically-inspired activities, but at the core, USAID does a lot of good work.

Similarly, the example of wells being built near chiefs houses. A few points: first, in other cultures, people don’t always see benefits going to leaders as an inherently bad thing (and neither do Americans now?! :/) When you are working within other cultures and governance frameworks, that arrangement could have potentially been the preference of the community. But assuming that was not the case, this example probably wasn’t very recent. Aid as we know it is a somewhat new industry and it’s also one very, very (perhaps too much) dedicated to analysing its own mistakes and changing how it operates. The issue of where the well was located is a well known problem from older programs that is comprehensively addressed nowadays. Programs need to demonstrate how they consult with communities to understand preferences, how they align with Sphere standards which outline how near to each house a water source needs to be, they need to go back and monitor how many people are using the well and get their opinions on how good the well is, they need to test the water and demonstrate some kind of handover plan for it’s ongoing maintenance.

So you can easily see how the bureaucracy expands to manage this. USAID don’t want shitty wells built all over the world, they want good ones. So there are more and more processes in place to manage projects in such a way to ensure good quality. All those steps I listed above need to be planned and explained by each recipient to USAID. USAID experts review the plans and sign off as to whether they meet standards. They also need to review the results of the monitoring and the outcomes. All of this quality control adds bureaucratic processes so it’s a catch 22 – yes, there’s a big bureaucracy but it’s about ensuring the funds are managed to the expected standards to best steward US taxpayer funds.

I could go on and I’ll certainly give the episode a second listen. I do really appreciate the coverage on this topic and hope to hear more. If you want any background on the sector or tips on who to contact, feel free to contact me.

Fantastic episode. This is by far the most comprehensive and balanced analysis of the situation I've come across. It is great that you both have field experience. I'm a former, (disillusioned) aid worker, and people who haven't worked in the field find it hard to understand the complexities of who benefits and how it can entrench existing power dynamics. Although I would be interested to hear the impact on local markets after the pause in the imported food aid. Are local produce prices driven upwards (assuming there's sufficient locally available) and do locals benefit, or does the cost of living spiral? I'm thrilled to hear this discussion, Great work, please keep them coming! A followup perhaps?